Biostimulants and climatic stress

Introduction

Climate change is profoundly disrupting agricultural systems. Rising temperatures, prolonged droughts, late frosts, occasional floods, and increasing soil salinization.

Worldwide, crops are facing a growing number of abiotic stresses that compromise their development, yields, and quality.

According to the FAO (2022), more than 50% of global yield losses are now caused by abiotic stresses—far more than by pathogens or nutrient deficiencies. The IPCC (2023) projects that by 2050, extreme climatic events could reduce yields by 17–22% in certain Mediterranean regions. In Europe, the Copernicus program confirmed that 2022 was the hottest year on record, with average losses of 10–20% for field crops in southern countries.

These events are no longer exceptional—they are becoming the new normal. Since the 1980s, the frequency of agricultural heat waves has tripled. Formerly fertile regions are now facing:

- longer and earlier water shortages,

- rising soil salinity due to intensive irrigation or rising water tables,

- extreme temperature fluctuations disrupting germination, flowering, and fruit set.

Faced with these upheavals, strengthening crop resilience is no longer an option but a necessity. The challenge is not merely to protect plants reactively, but to prepare them to activate their own defense mechanisms.

This is precisely the role of biostimulants: by modulating plant physiology, they help crops withstand and adapt to stress

The nature and mechanisms of abiotic stress

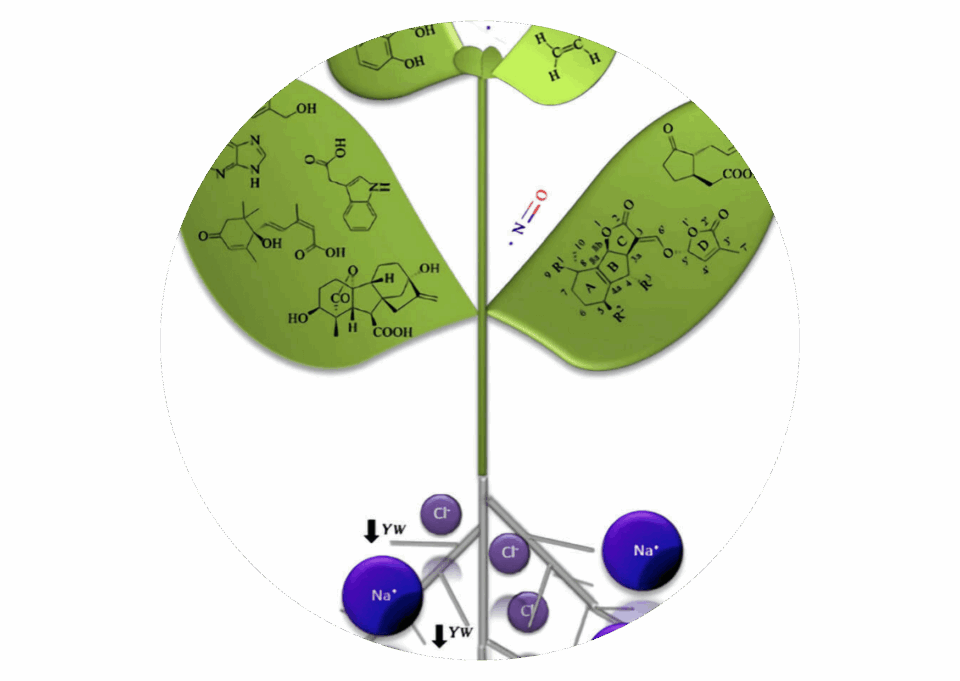

Abiotic stresses are non-living environmental factors that negatively affect plant growth, metabolism, and reproduction. They generally fall into four main categories:

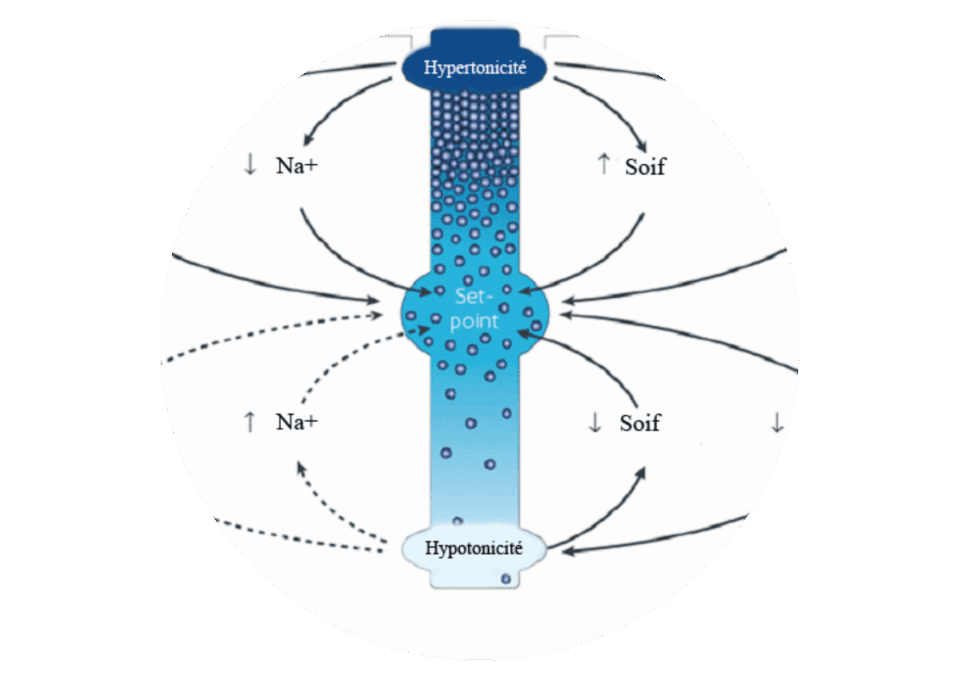

1. Hydric stress – caused by water deficit or excess, leading to osmotic imbalance, stomatal closure, reduced photosynthesis, and impaired nutrient uptake.

2. Thermal stress – heatwaves or frosts destabilize enzymes, damage membranes, and disrupt hormonal regulation.

3. Salt stress – accumulation of sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻) in the soil hinders water absorption and causes ionic imbalances.

4. Oxidative stress – often secondary to other stresses, results from the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that oxidize proteins, lipids, and DNA, accelerating cellular aging.

These stresses rarely act in isolation. More often, they trigger cascading reactions: stomatal closure limits CO₂ entry and photosynthesis; enzymes are inhibited, slowing metabolism; chloroplasts lose structure, reducing energy production; membranes break down, leaking ions and disrupting cellular balance; senescence pathways activate prematurely, accelerating decline.

Critical stages such as flowering and reproduction are particularly vulnerable. A heatwave lasting just 3–5 days during flowering can compromise fertilization and cut yields by up to 70% in sensitive crops like maize, tomato, or soybean.

Ultimately, plant survival and productivity depend on the speed and coordination of their defense responses—antioxidant, osmoregulatory, hormonal, and structural. The faster these mechanisms are activated, the more resilient the plant becomes when facing climatic stress.

Biostimulants: levers for crop adaptation

Biostimulants provide plants with a wide range of mechanisms to better withstand climatic stresses. Their effectiveness stems from the synergy of complementary actions, from immediate cellular protection to post-stress regeneration.

1. Activating the antioxidant system

Oxidative stress is a common consequence of drought, heat, or salinity, leading to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage membranes, proteins, and DNA.

Biostimulants rich in antioxidant compounds—polyphenols, flavonoids, organic acids, peptides—intervene by:

- stimulating the expression of genes encoding antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, APX),

- reducing lipid peroxidation and preserving membrane integrity,

- directly scavenging ROS.

For example, licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) extract applied to salinity-stressed beans increased chlorophyll content by 30%, reduced lipid oxidation markers (MDA) by 45%, and improved biomass (Rady et al., 2018). Similarly, garlic (Allium sativum) extract applied to eggplant and bell pepper under high temperatures (38–40 °C) boosted antioxidant activity and increased fruit production by 18% (Hayat et al., 2018).

2. Stimulating osmoregulation

Under drought or salinity, osmotic pressure drops, threatening cell turgor and enzyme activity.

Plants respond by producing osmolytes such as proline, glycine betaine, or trehalose.

Protein hydrolysates amplify this response: in maize, they doubled proline accumulation and stabilized photosynthesis under heat stress (Ertani et al., 2018). Extracts of white willow (Salix alba), rich in salicylic acid and flavonoids, also activate the GABA pathway and stimulate ABA biosynthesis, maintaining root growth under saline conditions (review 2024, PMC10967762).

3. Hormonal regulation and rebalancing

Abiotic stress disrupts hormone homeostasis: ethylene rises (accelerating senescence), cytokinins fall (reducing growth), and ABA is altered (modulating stomatal closure).

Plant extracts rich in triterpenic or phenolic acids help restore this balance. For instance, holy basil (Ocimum sanctum) extract promotes ABA synthesis, enabling finer regulation of stomatal closure and maintaining primary metabolism under water stress (Plant Growth Regulation, 2023).

Microbial strains such as Bacillus subtilis or Pseudomonas fluorescens add another lever: they produce ACC-deaminase, an enzyme that lowers ethylene levels by degrading its precursor, delaying senescence and sustaining growth. Trials in tomato and chickpea confirmed improved drought tolerance and more viable fruits (Backer et al., 2018).

4. Optimizing root development

Root system architecture is central to water and nutrient access. Deeper, more branched roots enhance drought resilience.

Humic acids, plant extracts rich in auxins or allantoin, and symbiotic microorganisms all support this development. For example, humic extracts increased maize root biomass by 24% and exploration depth by 19% under drought (Canellas et al., 2015). Comfrey (Symphytum officinale) extracts, rich in allantoin and rosmarinic acid, improved root biomass and leaf density in vegetable crops under moderate water stress (FranceAgriMer, 2022).

5. Supporting post-stress recovery

Resilience depends not only on resistance during stress but also on the ability to quickly resume vital functions afterwards.

Flavonoid-rich extracts, such as green tea (Camellia sinensis), accelerate recovery. In lettuce and bell pepper, they reduced membrane damage, stimulated chlorophyll biosynthesis (+22%), and enhanced expression of heat shock proteins (HSP70, HSP90), key for repairing damaged proteins (Frontiers in Plant Science, 2022). This recovery “boost” helps limit yield losses and stabilize crop quality.

Conclusion

In today’s context of climatic instability, biostimulants are not a replacement for conventional agronomic practices but a strategic lever to strengthen crop resilience. Their value lies in a preventive and adaptive approach that works with natural plant processes while respecting ecological balances.

By activating internal defense mechanisms—antioxidant, osmoregulatory, hormonal, and structural—biostimulants can:

- significantly reduce yield losses,

- enhance the quality and nutritional value of produce,

- and secure long-term resilience against climatic hazards.

When integrated into a broader agronomic strategy, biostimulants emerge as indispensable allies for modern agriculture: productive, sustainable, and resilient.

Have questions? Feel free to contact us—our team is here to help.

References

- Backer, R., Rokem, J. S., Ilangumaran, G., et al. (2018). Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: Context, mechanisms of action, and roadmap to commercialization. Frontiers in Plant Science, 9:1473.

- Canellas, L. P., Olivares, F. L., Aguiar, N. O., et al. (2015). Humic and fulvic acids as biostimulants in horticulture. Plant and Soil, 383, 3-41.

- Copernicus (2023). European State of the Climate 2022. Copernicus Climate Change Service Report.

- Ertani, A., Schiavon, M., & Nardi, S. (2018). Protein hydrolysates: New insights into biostimulant activity in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science, 9:1227.

- FAO (2022). The impact of abiotic stresses on global crop yields. FAO Report.

- FranceAgriMer (2022). Évaluation des extraits de consoude en maraîchage sous stress hydrique. Technical report.

- IPCC (2023). IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Hayat, S., Ali, B., & Ahmad, A. (2018). Application of garlic extract as a biostimulant under heat stress. Plant Physiology Reports, 23, 145-156.

- PMC10967762 (2024). Salix alba extracts and abiotic stress tolerance. Systematic Review.

- Rady, M. M., et al. (2018). Licorice extract as a biostimulant for beans under salinity stress. Egyptian Journal of Agronomy, 40(2), 87-102.

- Frontiers in Plant Science (2022). Flavonoid-rich extracts improve recovery of lettuce and pepper after heat stress. Front. Plant Sci. 13:10452.

- Plant Growth Regulation (2023). Ocimum sanctum extract improves ABA-mediated drought tolerance. Plant Growth Regul, 101, 65-78.

Disclaimer

This series is designed to share practical insights on biostimulants. Each month, we explore a new topic based on our expertise and research.